CBS News takes you to the world's northernmost community in Svalbard, Norway to experience what people there already know...

Arctic melting foreshadows America's climate future

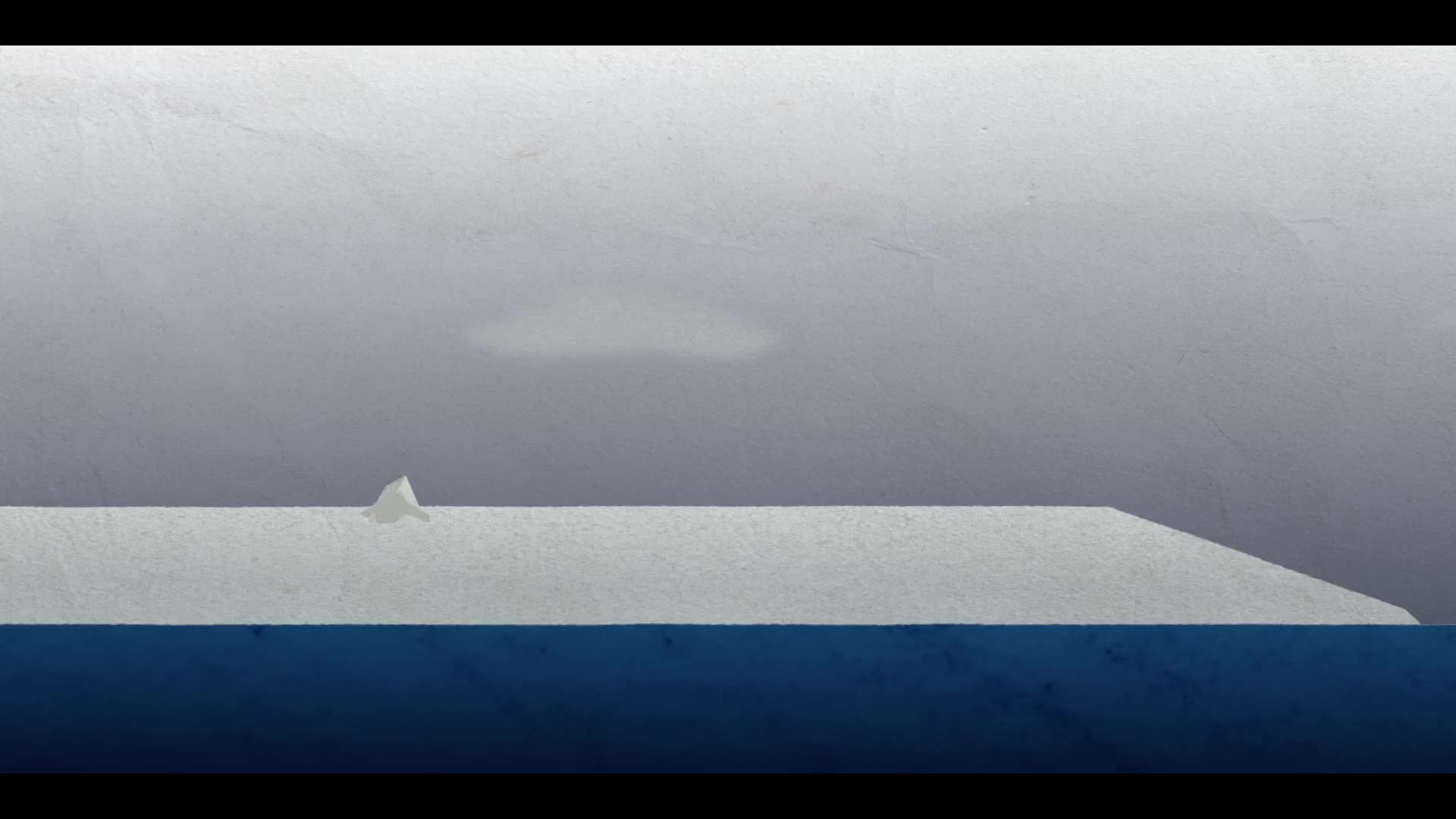

If you fly 4,500 miles from the United States over the Atlantic Ocean, deep into the Arctic Circle, you’re in Svalbard, Norway. It’s the most northern community in the world, where polar bears outnumber people.

It's also the fastest warming place in the world, and a critical scientific hub for climate change research. Getting to the remote research sites requires small planes, boats, helicopters, and even a cable car.

This project explores how the warming Arctic adds to rising sea levels along our U.S. coasts and instability in the atmosphere that contributes to our extreme weather events.

CBS News National Environmental Correspondent David Schechter presents On The Dot, a journey to see how we're changing the earth and how the earth is changing us.

Watch the documentary

Disappearing glaciers

In Svalbard, glaciologists like American Jack Kohler are documenting rapidly melting glaciers on Svalbard. Kohler has been documenting changes to glaciers on Svalbard for 27 years. During that time, he's watched the glaciers shrink before his eyes.

Jack Kohler

Jack Kohler

At the end of winter, Kohler lands on a glacier by helicopter to pound long stakes deep into the ice. Six months later, after the summer melting season, he returns to record how much of the stakes are now exposed. The more of a stake he can see, the more ice has been lost.

By 2100 the glaciers will be shrinking twice as fast as they are now, Kohler explained.

These photographs show how much the glaciers on Svalbard have changed over the last century.

Rising seas

Melting ice is speeding up the warming process, according to meteorologist Anna Sjöblom.

When ocean water is covered by ice and snow, most of the sun's rays bounce back into the atmosphere, shielding the water below from the heat of the sun.

Anna Sjöblom

Anna Sjöblom

Twenty years ago, when Sjöblom first started working on Svalbard, the deep ocean inlet at the edge of Longyearbyen would freeze every winter.

“It doesn’t anymore,” she said.

But in a warmer Arctic, the ice and snow are melting. Now, the sun can hit open water and heat it up. As that warmth spreads, it helps melt more snow and ice, and the loop accelerates.

That's the main reason why the Arctic is melting 3-4 times faster than the rest of the world.

CBS News local journalists explored how increasingly volatile winters, caused by climate change, are affecting their communities across the country.

NASA's SWOT satellite revolutionizes scientists' ability to forecast sea level rise

CBS News Los Angeles reported on new research allowing scientists to forecast sea level rise, helping residents anticipate whether their property could be at risk. Read more

Port of San Francisco, US Army Corps of Engineers plan to raise landmark Ferry Building due to rising sea levels

CBS News San Francisco reporter Juliette Goodrich explained how an important landmark is threatened by rising sea levels. Read more

Stafford Township, New Jersey helping residents elevate homes to combat rising sea levels

CBS News New York reporter Vanessa Murdock reported on how one town in New Jersey is helping homes located just feet from the water, threatened by rising seas. Read more

Philadelphia neighborhood faces floods, tough choices as climate crisis hits "Planet Streets"

CBS News Philadelphia reporter Brandon Goldner showed how a majority Black neighborhood in Philadelphia is a microcosm of the decisions communities on planet Earth will face because of climate change. Read more

Ocean City at risk: Rising sea levels threaten Maryland's summer getaway

CBS News Baltimore reporters Paul Gessler and Rachel Gold found rising sea levels and coastal erosion threaten popular vacation destinations near Ocean City.

Sea level case study: $1.2 billion of property at risk along Maryland shoreline

CBS News Baltimore Data Journalist Rachel Gold worked with scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey to pinpoint exact areas along Maryland's eastern shore susceptible to change over the next decade due to hazards along the coast, including erosion and rising sea levels.

Reporters discovered thousands of individual land plots susceptible to sea level rise and coastal erosion, representing a total value of over $1.2 billion. The majority are homes, businesses, and places of worship. Some structures are more than a century old.

Over 70% of the affected parcels are in Ocean City, home to countless hotels, coastal shops and stores all built along the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and feeling the effects of its strength. Read more from CBS News Baltimore

Volatile winters

Despite frigid winters, Svalbard rarely sees extreme snow. When it does snow, it's usually light.

But in January 2015, a major storm hammered Svalbard with blinding wind and snow.

In some places, more than 16 feet of snow fell in 12 hours, triggering an avalanche — the first to ever do serious damage to Longyearbyen, the largest settlement on Svalbard.

Homes were ripped off their foundations and left in a pile. Two people died, one of them a young girl.

Lena Nagell Ylvisåker

Lena Nagell Ylvisåker

"That made a huge impact on me. I knew that little girl, she went to kindergarten with my daughter so it was really close. And hard to understand, really, that it happened."

Martin Indreiten

Martin Indreiten

The increase in avalanches forced some Longyearbyen residents like Martin Indreiten to get creative and find solutions.

His team at the Arctic Safety Center built barriers to protect the town from future disasters.

They also built low-cost, snow depth sensors that are now deployed on the steep slopes around town. Each device sends back hundreds of measurements a day, giving safety managers better insights into avalanche risk and when to issue evacuation orders.

Indreiten believes avalanche-prone communities around the world, including the U.S., will benefit from the technology developed on Svalbard.

Similar adaptations may be needed in the U.S. as temperatures continue to rise and winter weather becomes more volatile.

Like in Svalbard, the U.S. has experienced warming winters in recent decades. Nationally, temperatures have risen more than 3° on average Fahrenheit since 1975. They're up more than 13° in Svalbard.

CBS News local journalists explored how changes to winter weather are affecting their communities across the country.

Climate change impacting Lake Winnipesaukee ice-out and ice-in dates

CBS News Boston reporter Jacob Wycoff explained how warming winter temperatures are affecting the ice fishing season for local residents. Read more

Pittsburgh's erratic winters' impact on the snow removal business

CBS News Pittsburgh reporter Ray Petelin found decreasing snowfall is threatening the jobs of snow plow drivers. Read more

Warming Michigan winters and snowmobile tourism

CBS News Detroit reporter Ahmad Bajjey reported more warm winter days are wreaking havoc on the snowmobile tourism industry. Read more

Warming climate in Chicago expected to bring even more unpredictable winter weather

CBS News Chicago reporter Tara Molina explored the many ways volatile winters are impacting the region. Read more

Lake Superior, known for icy waters, one of the fastest warming lakes in the world

CBS News Minnesota reporter Erin Hassanzadeh found that a rapidly-warming Lake Superior is damaging fish populations and causing more harmful algal blooms. Read more

Reservoir empty, farm wells retired amid high demand for water on Colorado's Eastern Plains

CBS News Colorado reporter Karen Morfitt found warming winters mean less snow, which is contributing to droughts that are likely to worsen. Read more

Skiing in the uncertainty: How Northern California ski resorts keep up with a changing climate

CBS News Sacramento reporter Ashley Nanfria reported milder winters and a changing climate have meant less snow at ski resorts near Lake Tahoe. Read more

Greenhouse gas emissions

In the Arctic, warming winters and the disappearance of Svalbard's glaciers is creating another problem: the release of methane from deep underground.

It's a potent greenhouse gas with more than 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide over 20 years, according to professor of glaciology Andy Hodson.

Andy Hodson

Andy Hodson

He’s documenting how ancient methane, trapped deep underground, is escaping at the edge of glaciers as they retreat.

Hodson and his colleagues at the University Centre in Svalbard have measured 123 springs around Svalbard and found methane in all but one.

Normally, permafrost prevents methane trapped deep underground from entering the atmosphere. But there's no permafrost under a glacier.

When the glacier melts, the methane trapped beneath is released.

Recently, six of the 10 largest emitters of methane, including the United States, pledged to reduce their emissions by 30%.

The methane that is now increasingly bubbling up through melting ice wasn't factored into those pledges.

That means countries may need to take even more drastic action to reduce their own methane emissions, according to Hodson.

“If there's a huge natural rush of methane about to come, then that will change our planning for methane management.”

If countries don't cut their methane emissions further, it will accelerate an already worsening problem. Since 1980, the amount of methane in the atmosphere has increased 165%.

That's an even more rapid increase than carbon dioxide, which has increased 50% over the last four decades.

Ove Hermansen, a senior scientist with the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, is one of a network of scientists around the globe who gather air pollution data.

Ove Hermansen

Ove Hermansen

Hermansen coordinates with a global network of observatories, including one on top of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii.

When scientists compare the extremely detailed readings collected from each site, according to Hermansen, they all see the same thing: soaring levels of greenhouse gases.

"Air pollution doesn't see any borders. The increasing levels of carbon dioxide [in Svalbard] are caused by emissions in Norway, in Europe, in China, in the U.S., everywhere."

Those emissions are caused by humans. They come from our cars, our factories, and from producing oil and gas. They are the reasons our climate is changing, both in Svalbard and the United States.

"Of course you can get sad or frustrated. But then you have to think about all the positive things that are happening. And there's still a chance to turn this around."

Copyright ©2023 CBS Interactive Inc. All rights reserved.